by Victoria-Strauss for Writer Beware® June 10, 2022, reprinted with permission

It should probably go without saying that you don’t want your publishing contract to include clauses that contradict one another.

Beyond any potential legal implications, internal contradictions suggest a publisher that either doesn’t understand its own contract language well enough to spot the problem, or a publisher that simply doesn’t care. Neither is a good sign for what lies ahead.

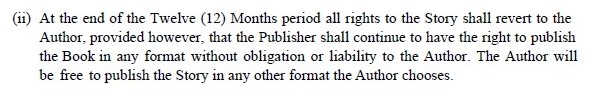

Contradictions can be tricky to spot, especially for first-time authors not experienced in contract legalese. Here’s an example that came across my desk recently: an anthology contract from Dark Lake Publishing that provides for rights reversion 12 months after publication:

Side note: this is a crap reversion clause, since it not only allows the publisher to keep publishing indefinitely but doesn’t say anything about paying for that privilege. That’s not the issue I’m highlighting in this post, however.

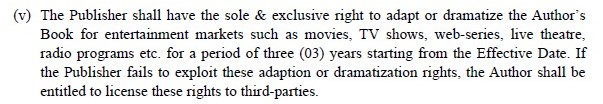

The wording of the clause seems pretty clear, right? All rights other than publishing rights–and this is an all-rights contract, with the publisher laying claim to “all Intellectual Property Rights subsisting, either in present or in the future, in the Book in all formats”–return to the author 12 months after the contract’s effective date, which is the date of publication. But a few clauses down, there’s this:

But…but…if all rights other than publishing rights revert after 12 months, how can the publisher lay claim to dramatic rights for two more years? It’s a clear internal contradiction.

In practical terms, there’s probably no impact: this particular publisher has about as much ability to exploit dramatic rights as I do of space-traveling to Mars. But what does it say about a publisher that either hasn’t spotted the cognitive dissonance, or is perfectly fine with it?

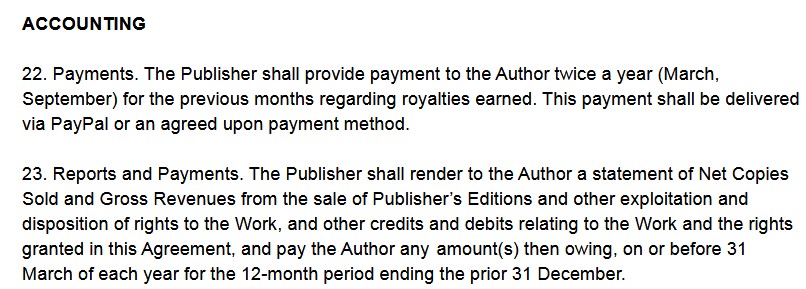

Another example I’ve seen recently involves royalties. This contract from Fractured Mirror Publishing appears to plan to pay both twice a year and once a year:

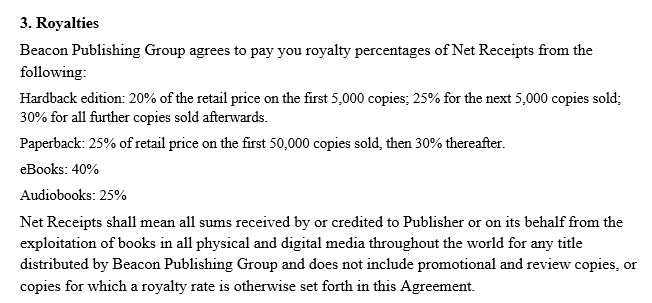

Here’s more confusing royalties language from Beacon Publishing Group, which first promises to pay based on Net Receipts, but then cites percentages of retail price (guess which one will appear in your royalty check):

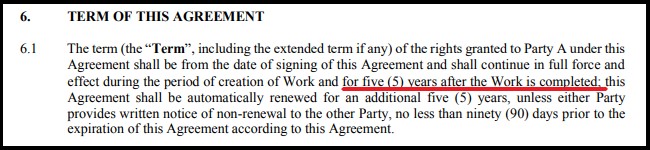

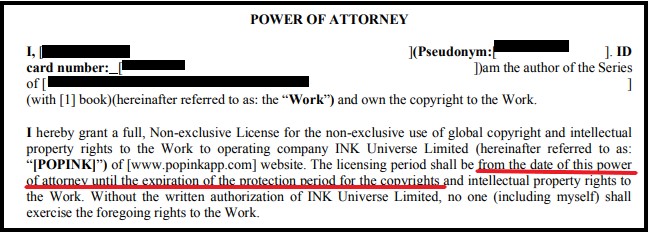

Another example: serial reading/writing app Popink, whose contract appears to extend for a limited term, but includes a Power of Attorney clause at the end of the contract that claims rights for the duration of copyright (read more about Popink’s awful contract here).

But the internal contradiction that I see most often, and most consistently, involves copyright: contracts where the grant of rights explicitly transfers copyright to the publisher, while further clauses acknowledge copyright retention by the author.

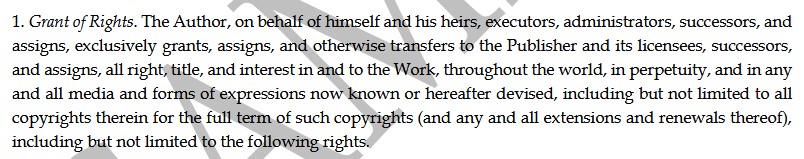

Here’s what I’m talking about. These clauses come from the contract of Histria Books.

The key wording here is “exclusively grants, assigns, and otherwise transfers to the Publisher…all right, title, and interest in and to the Work…including but not limited to all copyrights therein”. Whenever you see language like this, it means you are agreeing to give up ownership of your copyright.

Histria’s contract includes language allowing for termination by the author under certain circumstances, so the copyright transfer is temporary rather than permanent, which doesn’t necessarily make it a better deal. However, when you transfer your copyright to someone else–even temporarily–that someone becomes the owner of all your intellectual property rights, without exception, for as long as the transfer is in force, and can do anything it wants with them, from licensing rights to third parties to creating sequels, spinoffs, and derivative works.

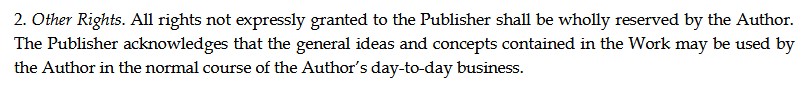

So you have to wonder why Histria’s copyright transfer language is followed by this:

In a contract with a conventional grant of rights–one that does not include a copyright transfer–you want to see such a clause, to make clear that the publisher can’t claim any rights not specifically mentioned. But Histria’s contract does include a copyright transfer, which means that there are no rights remaining that can be reserved to the author. If not outright contradictory, this clause is certainly inconsistent. But then there’s this:

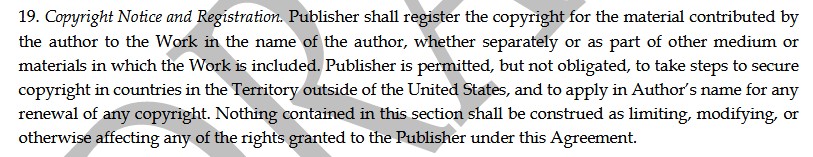

But wait–didn’t the Grant of Rights make Histria the owner of the copyright? So why would it register in the author’s name? To do so would acknowledge the author as the copyright holder, since copyright registration is made in the name of the copyright owner.

Side note: what the hell is meant by “material contributed by the author to the Work”? Wouldn’t that be, hmmm, the work itself, given that the author wrote it? Even if nothing else in this contract were problematic, this bizarre wording demands an explanation.

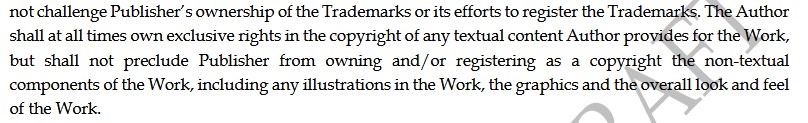

Finally, there’s this–a pretty unambiguous acknowledgment of the author’s copyright ownership:

Bottom line: multiple clauses in Histria’s contract are inconsistent with or directly contradict the copyright transfer in Clause 1.

I have no idea what the legal ramifications are here. If there’s a dispute, whose ownership would prevail: Histria’s, per Clause 1, or the author’s, for which registration in their name provides prima facie evidence? Regardless, such inconsistencies really should not exist in a publishing contract, and their presence raises the questions posed above: does the publisher not understand its own contract? Not a good sign of professionalism or expertise. Does the publisher not care? Ditto, and you have to wonder what else it doesn’t care about. Worth noting: I’ve heard from authors who contacted Histria about the copyright contradictions, and were brushed off.

This confusion over copyright transfer is more common than you might think. Other publishers whose contracts include it: RIZE, J. New Books, Assure Press, Silver Bow Publishing, Realmwalker Publishing Group, Walnut Springs Press, Pen-L Publishing, and the two publishers that are the subject of Michael Capobianco’s recent post. I have been asked not to use their names to avoid identifying the sources. The troubling contract clause that Michael discusses actually is consistent with a copyright transfer, but not with the publishers’ promise to register in the author’s name. Interestingly, several of these contracts appear to have been adapted from the same template.

So what’s the moral of this post?

Obviously, unless you’re doing work-for-hire, don’t sign a publishing contract that involves giving up your copyright. More broadly, though, it’s incredibly important to go over any contract you’re offered with a fine-toothed comb, and not to ignore any inconsistencies or contradictions (as authors, swept up in the excitement of a publisher’s validation, too often do). Writer Beware is glad to provide non-legal advice. We’re not lawyers, but we are professional writers, and we’ve seen a lot of contracts over the past 20+ years.

What about negotiation? Especially in the small-press world, publishers can seem resistant to negotiating, but sometimes may be willing to remove or change problematic contract terms. However, even if they are, you really need to ask yourself what it says about the publisher, and its view of its authors, that it would offer poor contract terms to begin with.

And if you do spot problems, and the publisher is unable to satisfactorily explain them–or, worse, tells you not to believe your lying eyes–move on.

Wonder if a publisher is legit? Check out the archived list at Writer Beware.

Victoria Strauss, co-founder of Writer Beware®, is the author of nine novels for adults and young adults, including her Way of Arata epic fantasy duology, and a pair of historical novels for teens, Passion Blue and Color Song. She has written hundreds of book reviews for publications such as SF Site, and her articles on writing have appeared in Writer’s Digest and elsewhere. In 2006, she served as a judge for the World Fantasy Awards. She received the 2009 SFWA® Service Award for her work with Writer Beware®, and in 2012 was honored with an Independent Book Blogger Award for the Writer Beware® blog.