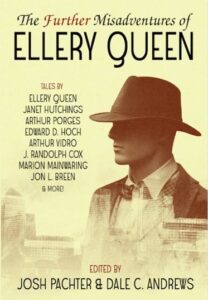

by Arthur Vidro, from the Summer 2017 issue of Calliope, reprinted with permission.

by Arthur Vidro, from the Summer 2017 issue of Calliope, reprinted with permission.

In the 1980s, I was fortunate to work as part of the copy-editing team at a national weekly trade newspaper. There were no e-issues then; just real newsprint on real paper.

Our tasks included fixing mistakes, conferring with writers for clarifications, and adding headlines.

My favorite work involved cutting the articles and columns to fit the predesignated spaces. The other editors tended to follow the journalism tradition of cutting articles from the bottom. I preferred a more artful approach: delete a word here, a clause there, a full sentence yonder, occasionally an unneeded paragraph. Often the writers never realized I made any cuts.

This approach works with fiction, too. In the late 1990s I learned of a well-paying magazine serving the casino industry. Their needs, beyond the usual articles on casino construction, management, promotion, regulation, etc., included one piece of fiction per issue. I sat down and wrote “Murder at the Roulette Wheel,” a fair-play murder mystery. It’s hard to remember now, but I believe the first draft ran about 1,800 words. For me, that’s sparse and trim writing.

Trouble was, the magazine had a limit of 700 words. I began to cut. And cut. And cut. Which of my lovely words weren’t truly needed? More than I originally thought.

Each subsequent version had fewer words. And, to my amazement, the story improved. When one cuts fat from a story, the story flows better.

I got down to 1,000 words without problem.

But the final cutting of 300 more words, well, I wasn’t totally happy with the result. At this point it felt like cutting muscle, not fat, so the story suffered a bit. But I got it down to the 700-word limit and mailed it off.

The rejection letter was nice, saying the story was very close to meeting their needs and to try them again. Alas, I didn’t try them again (I had only the one casino-story idea) and eventually sent the 700-word version to Calliope, which published the tale in 2002.

Let’s skip to 2017.

I’ve become a freelance editor/proofreader, and occasional writer, trying to find clients. A retired gentleman named Bill sent me a murder story that involves fishing. It ran 9,816 words and had already been rejected by Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. He wanted to know if and how I could improve his story. We agreed on a small fee to have me edit the first third of his tale. Here’s a paragraph I changed:

Before Editing:

Heading home on Route 32, crossing the Ware River she thought of how the evening rise would begin soon and she decided to do a little fishing. Her husband wouldn’t be home for dinner—as he had to be at a selectmen’s meeting for a client whose used car sales license was in trouble in Athol on the Cow Hampshire border. They lived in Dudley on the Connecticut border. She’d be lucky to see him by midnight.

After Editing:

Heading home on Route 32, crossing the Ware River, she decided to do a little fishing. Her husband wouldn’t be home for dinner—he had to be at a selectmen’s meeting way over in Athol. She’d be lucky to see him by midnight.

Which version flows better?

Of course, before making any changes, I considered the tale as a whole. The husband, a lawyer, would play an important role, but the specifics of his workload and clientele were all irrelevant.

Bill agreed I’d improved the first third of his tale and offered to pay me to edit the full story, provided I came up with another publisher to send it to. He specified it had to be a print publisher, not an online venture.

I knew of many mystery anthologies seeking tales, all with a 5,000-word limit. Bill’s tale was practically twice that limit. No way could we cut it to 5,000 words . . . or could we? I played with the idea. Then the prospect excited me. I hadn’t cut to meet a word count since the twentieth century. Without consulting Bill, I decided to cut the fishing mystery to 5,000 words, just for the challenge, to see if it I could do it. In case I failed, Bill need never know.

Found one scene that could be deleted entirely. One of the minor characters could also be expunged, if the one vital sentence he uttered could be transferred into another character’s mouth. It was easy to cut away 2,000 words, and the story was improving. Then it got tricky. I decided to cut the first two pages, including the entire paragraph quoted above, where the protagonist decides to go fishing, detours to the water, changes clothes, finds the best spot, and begins to fish. Instead, I began with page three, with the protagonist making her first cast. And still the story improved.

Each subsequent printout contained progressively fewer words, which I wrestled with to find further places to prune.

I think the version with 6,012 words was the best. With the fat mostly gone and I deleted muscle—elements such as characterization, worthwhile detail, romance, and humor.

At last I reduced the story to 5,000 words. Only then did I approach Bill and offer to edit the tale down to 5,000 words for a fee. He agreed, and the story has since been submitted to three mystery anthologies. It still might not get published, but at least now Bill has a version of the story to submit whenever the opportunity arises.

Most of our stories contain fat and will flow better without it.

Arthur Vidro is a freelance editor/proofreader/writer and has sold eight short stories and hundreds of newspaper articles.