by Constance Hood

by Constance Hood

What a boring world it would be if everyone were perfect. People would stack up in our lives like a bunch of Lego bricks, with uniform strengths and clearly defined edges. Writers build stories, but stories are not made of interchangeable characters. We look into ourselves and at the people who have been closest to us, hoping for some greater understandings. From there we conjure up the scenarios. Personal flaws and foibles have the best chance of reaching readers’ minds and hearts, and of engaging readers in a character’s trajectory. Readers like the edges of life. If we think we can entertain or instruct others, we share our stories with an audience, and that’s when we take some risks.

I was asked to describe how historical-fiction writers do this without offending family members or friends. When you’re writing a story, it’s difficult enough to get your own understandings down on paper. Others’ sensibilities can’t be a major concern in early drafts. People rarely see themselves as characters, and I will make changes as I go along. Like characters, our loved ones have an exterior life that they present. We go through a pretty intrusive process to dig away at their interior thoughts and desires.

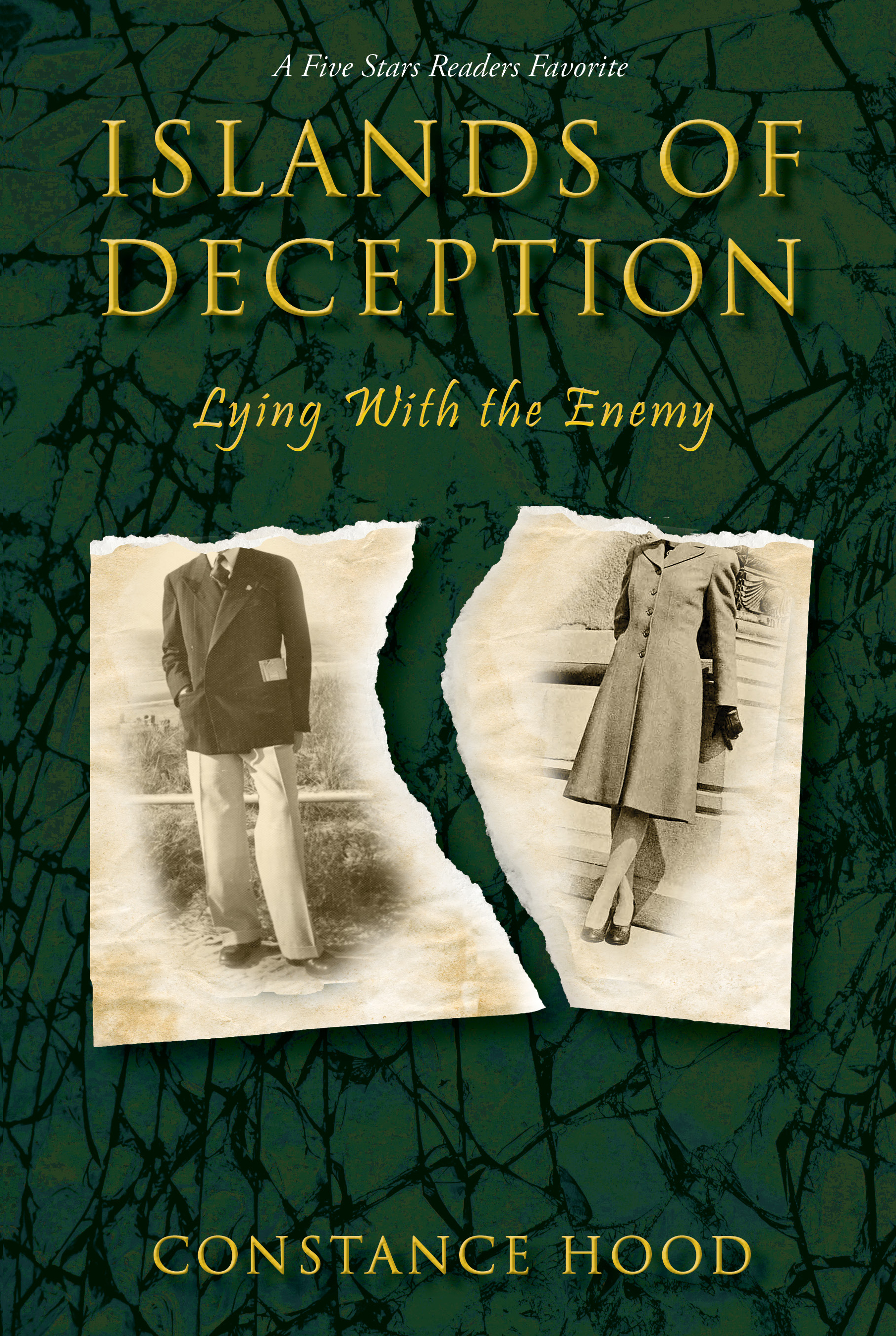

In rare instances we meet a person whose story needs to be shared. Islands of Deception: Lying with the Enemy is based on true stories. My estranged father put a packet of notes into the mail, about 12 single-spaced pages. Dad was a spy and it was evident that he took pride in his work. Was this story even true? Authentic tales of espionage during WWII were something that he could not disclose. Spying is quiet work. Coupled with his story was my aunt’s account of her life during the war years. For more than 50 years my father and his sister had raged against fortune and accused each other of lies and cheating. Their only agreement was this: Layers of secrets could not be revealed to their spouses or their children. There were reasons for the lies and for decisions that they were forced to make as young adults, Jews in a Europe gone topsy-turvy with persecution and war. After many extended visits to Holland, as well as a foray through U.S. Army counterintelligence records, it was made evident to me that both brother and sister were speaking their truths and that they were telling the same story. It was not a pretty one.

In rare instances we meet a person whose story needs to be shared. Islands of Deception: Lying with the Enemy is based on true stories. My estranged father put a packet of notes into the mail, about 12 single-spaced pages. Dad was a spy and it was evident that he took pride in his work. Was this story even true? Authentic tales of espionage during WWII were something that he could not disclose. Spying is quiet work. Coupled with his story was my aunt’s account of her life during the war years. For more than 50 years my father and his sister had raged against fortune and accused each other of lies and cheating. Their only agreement was this: Layers of secrets could not be revealed to their spouses or their children. There were reasons for the lies and for decisions that they were forced to make as young adults, Jews in a Europe gone topsy-turvy with persecution and war. After many extended visits to Holland, as well as a foray through U.S. Army counterintelligence records, it was made evident to me that both brother and sister were speaking their truths and that they were telling the same story. It was not a pretty one.

How they might have felt about their characterizations was not part of any creative decision in the book. If I were restricted by “What might grandfather think about this?” I would never write another word. This story would not be served if these were simple people with reasonable experiences. More than a year after sending the manuscript to agents, I knew why the story had to be told. It was more important than the individual narrators. The approach of worldwide fascism in 1939, and the responses of the characters, is highly relevant to us.

I decided that the accounts of my father and aunt needed to be a part of our larger universal story. The stories of immigrants are larger than the individuals. The experience of the Jews is larger than entire communities. My two Dutch teenagers came of age in a world that offered them existential questions, pain, and loss. They were a part of a larger community of thousands of families; people who were forced to leave their homeland and live in exile. These stories of exile, emigration, and the rending of families needed to be told. They come complete with the anger, complete with sores, with the scabs, and complete with the scabs picked open.

Islands of Deception: Lying with the Enemy took on a life of its own. Forget the outlines and forget the storyboards. These are full-bodied dimensional people. There’s tenderness, there’s rage. Awful things happen, good things happen. Since my father and aunt had lived their lives in secrecy, I had to construct the scenes from their words and actions over the years. The ups and downs of life play themselves out whether they are in a comfortable home, in an army barracks, or in a concentration camp. We have to listen to the characters’ experiences. Revealing the human story means that we have to invade privacy.

Your story has life on its own, and your characters are simply actors.

- Go ahead and change names.

- Change a gender when you can.

- A few physical characteristics or mannerisms can also help. I made my character a beer drinker, and my father hated beer.

- Make sure that significant events of the time are accurate. That helps readers make connections to what they know.

Before I submitted my manuscript, I asked friends to do some table readings. Readers wanted to tell their stories too, which I saw as a good sign. We ended up with our real people and their imaginary friends, who aren’t really all that imaginary.

One of my favorite characters is a cat. Hans Bernsteen has to somehow arrive in the South Pacific as a civilian. His cover is that he has been dropped off from a Dutch merchant marine ship. I knew someone whose father was a Dutch merchant captain during the war. My friend Ina and I sat at her coffee table for a couple days going through marine records, books, logbooks, photographs, just to see “What did that look like? What kind of work was done on the ship? What is a convoy and why was it so dangerous?” Ina described a horrific torpedo attack. While the men are preparing the ship for a hit, Mickey the cat is racing to move her kittens to safety. Mickey’s sense of fear and protection told us so much about the attack on a convoy, waves of fear that traverse miles of deep water. Then, another reader told of his uncle working endless hours in sick bay taking care of shipwrecked victims covered in burning fuel.

These stories grew, and I think my final interview was absolute gold. I was reworking the end of the book and had a chance to spend an afternoon with someone who had been a member of the German army. After about an hour, his son picked up the bottle.

“Here, have some more wine.”

“Oh, I’m fine, I don’t need any more.”

Chris poured. “Yes, actually you do. Anti-Semitism is coming up next.”

So, we went for it. The old soldier talked, and I recorded.

Ultimately our stories are all about the reader. One review comes to mind, written by a family member who did not read the manuscript until Islands of Deception: Lying with the Enemy was published.

“I was captured with the vividly painted scenes of stories I knew to be true as a family member. Reality is often outrageous, and that is what Constance has so artfully depicted with her emotionally accurate tale of hard choices and unexpected outcomes. Her book has soul, captivating characters, and realities that leave you shaking your head.” —Nancy Hall

So, go ahead, face your people, and serve your story.

Constance Hood has earned professional credits as an artist and a writer in both theater and classical music. Her day job was as a LAUSD literacy expert, educating students from “Which way do you hold the book?” through Advanced Placement Writing skills. Islands of Deception: Lying with the Enemy is her second historical novel.