by Gila Green

by Gila Green

Like millions of other authors, I write because I have a message I’m passionate about; I want to express myself to the world. The problem with long and complicated messages is that people suffer from denial and refuse to hear them; they don’t buy books to read sermons; and preaching can engender resentment, comes across as heavy-handed, and reads as though you’re talking down to your audience. These are all things successful fiction authors avoid.

Simply put, a message is not something you want in a novel, particularly a young adult novel. Young people read fiction to visit other worlds and ideally lose themselves in them, not tour the author’s personal lecture hall.

So, what if you have a timely, sensitive, controversial topic you’re passionate about and want to turn into young adult fiction? How do you delight your readers instead of dismay them?

Here are four ways you can effectively write young adult fiction with a message and still win with your audience:

1. Just tell the story

The best young adult novels are great stories. They have all of the elements of stories worth remembering and passing on to others: suspense, drama, villains, heroes, humor, excitement, transcendence. I could go on, but you get the idea. If you concentrate on writing a great story, your message will come through on its own. Don’t waste time pondering your message beyond your initial need to clarify your novel’s goals.

Nobody ever suggested that at the end of The Wizard of Oz there should be a monologue about how the traits we need are already inside us. The audience understands on its own that the lion was already brave before he ever asked the Wizard for bravery because the story is so well told and the characters so richly developed.

2. Make your character likeable

Your message won’t be heard if no one likes your messenger. There are a number of ways to create likeable characters. The most obvious is to make your character a nice person—the one who can share the last glass of cold water in a heat wave, protect someone more vulnerable from a bully, or dive into the river to save a puppy.

A second excellent way is to use a little psychology. As human beings we long to be more attractive, more loved, stronger, smarter. Fulfill that longing by giving it to your character and she will have instant likeability.

How do you do that? Write a protagonist who excels at something, and it doesn’t have to be magical or a super-power. She can be the smartest girl in the class or a top gymnast, an admired artist or winning athlete, but she has to be amazing at something that your readers covet. She can be the type of person others automatically go to for advice, if you think that’s the sweet spot with your audience. Ask yourself what your ideal readers long for and make sure your heroine has it in spades.

Number three on the create-likeable-characters list is to give your character worthy goals. We pay more attention to people we admire, so if you want your message to come across, make sure your messenger is admirable as well as likeable.

How do you do that? Give your protagonist commendable goals. If your heroine’s goal is to work after school for the sake of flaunting her fashionable clothes at the school dance, you will lose your reader. On the other hand, if your heroine wants to work three after-school jobs to help build an orphanage, school, or hospital, your readers will be with you.

Finally, make sure your character has some sort of vulnerability (remember Superman’s kryptonite). There are endless ways to make your reader feel sorry for your character. Orphans are cliché but still work well; just ask Harry Potter. You can use disability, poverty, or even hurt feelings (her best friend chooses someone else to be her partner for an important project) to engender the weakness your heroine must have.

3. Weave your themes tightly

The more developed your theme and subthemes, the stronger your message will be without the need to resort to preachiness. The theme is your subject matter. It answers the question: what is this story about? (It doesn’t answer the question: what happens in the story?)

The more developed your theme and subthemes, the stronger your message will be without the need to resort to preachiness. The theme is your subject matter. It answers the question: what is this story about? (It doesn’t answer the question: what happens in the story?)

If your theme is love conquers evil, stay on point throughout your story, make sure there is something to reinforce this theme in every chapter, and your message will ring loud and clear. Review your chapters in your revision and ask yourself if your theme is present in each.

4. Create a character with opposing views

An excellent way to ensure your novel doesn’t come off as preachy is to create a character with views that oppose those of your heroine, who presumably represents the message you are really trying to convey, though this does not have to be the case.

You can even create more than one character with a third view. Don’t overdo it; any device that is overused can backfire, as it calls too much attention to itself.

Presenting more than one view on a subject gives your novel balance and depth. The key here is to make sure the opposing view has some legitimacy.

For example, if you have one character who strongly believes in individualism and that’s the message you want to convey, create an opposing character who argues that the collective is more important than the individual.

Both of these views have legitimacy, and that’s why this method works. Your heroine might argue that students must be able to express their individuality, and she might be passionately against mandatory school uniforms that, she argues, limit self-expression.

As the author, you create an opposing character who disagrees. You could set up a school debate in which the opposing character claims that school uniforms are necessary because many students feel pressured to dress a certain way, and that ultimately uniforms save parents money.

These are legitimate arguments and are worthy of the reader’s consideration. Ultimately, if your true message is that expressing individuality trumps all, your heroine can win the school debate. In this way you have avoided preachiness, but your message is clear.

It’s important to know that most writers discover messages in their works that they never consciously planned to be there. Those messages organically grew out of the successes and failures of the characters. It is those unplanned messages that are the most influential on the audience, the ones that will resonate long after the last page has been read.

The cover blurb for No Entry.

Brokenhearted after losing her brother in a terrorist attack, 17-year-old Yael Amar seeks solace in an elephant-conservation program in South Africa’s Kruger National Park.

Catapulted into a world harmonious with nature, and dazzled by her new best friend, Yael reunites with her devoted boyfriend and becomes fascinated by a local ranger. Then she sees something shocking.

With her newfound heaven now seething with blood and betrayal, she must keep a secret from the people she loves most in order to protect them, and stand against the murderous forces that threaten Kruger. But will taking a stand do more harm than good?

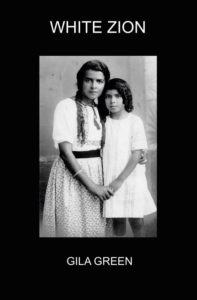

Canadian Gila Green is the author of White Zion, Passport Control, and King of the Class (available on Amazon), as well as dozens of short stories. No Entry is the first in an environmental, young adult series in which a Canadian teen heroine takes on a murderous poaching ring in South Africa’s Kruger National Park (launches September 1; available for preorder now). Currently she works on the sequel titled The DroneZone.

Thanks so much for hosting me on your site.