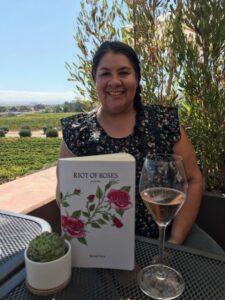

by Brenda Vaca

by Brenda Vaca

Hispanic. Latino. Latina. Latinx. Latine. Mexican. Mexican American. Chicana. Brown. Indigena. Xicana.

In the words of Chicano writer, David Bowles, when it comes to identifying people he writes: “Basically, be precise. Don’t misuse labels. Educate yourself.” For me it’s a good opportunity to build relationships. Not bridges but relationships. The last thing racialized people want is to be categorized and then miscategorized. So in that spirit, I will share with you precisely who I am.

Over the years, what identifying word to use has been heavily informed by the company I keep. No more. Now I choose to use the word I feel most comfortable with—it is who I am, not as others see me, but as I see me: Xicana.

When filling out the census, or other optional ethnicity questions on official forms, it had historically been an existential crisis. Who am I? What am I? Who gets to name who I am? Hispanic, as you probably know by now, is an identifier that appeared during the Nixon era. It is an all-consuming monolith, a valuable piece of demographic information, and an attempt to target an audience.

But what if the audience is tired of being targeted? Truth be told, I reject the identifier hispanic. It is a label I do not use, although I confess I allowed others to thrust that identity on me in the past. Mostly in church community settings when I was active in the ministry. In fact, my last ministry job was as a missionary for churches working with hispanic communities and the debate went on and on as to who should be included in that category.

The truth is I’ve always known who I am. I grew up in a Mexican-American family. My father, the youngest son in his family, was born and raised in Jocotepec, Jalisco, Mexico. When he was three years old his mother died. Looking at old photos of her—the very few we have— shows a young indigenous woman. What tribe, I wonder. Reading and research suggests our people came from any one of the Chichimeca Nations: Cocas, Purépecha, Otomi, etc. That part of me is yet to be uncovered.

My mother, on the other hand, was born to a Mexican family from Pénjamo, Guanajuato, Mexico in Watts, Los Angeles during the Great Depression. She is a Chicana who is proud of where she comes from—her Mexican roots and her U.S./American upbringing. She grew up filling out the U.S. census forms and other survey questions over the last eight decades and is identified on her birth certificate as White. Let me tell you, she is not a white woman. She is a luscious brown, the color of cilantro seeds, as I wrote in one dedication poem to her.

I share all this with you in my attempt to convey why one’s personal and familial history is important, especially when it comes to celebrating heritage. Equally important is one’s own lived experience. I have been identifying as a Chicana since I was a teenager in high school. My brother, the first in our family to go to college, came home from his first semester at U.C. Berkeley with a reading list after taking a Chicano Studies class. My brother, a teacher with the Los Angeles Unified School District, now in his twenty-eighth year of teaching, has always handed down his reading lists to me, his baby sister. We are four years apart and my oldest brother, a natural teacher, used to love to give me assignments. As a teenager that meant I was reading Occupied America: A History of Chicanos by Rudolfo Anaya, Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street, and Lorna Dee Cervantez’s Emplumada. I came to understand this time as the awakening of my Chicana consciousness. In the 1990s, I participated in a Quaker youth group, and I wrote in my journal and dabbled in poetry late at night. Words became my everything. My parents, self-employed, ran a small Mexican restaurant in the City of Orange. I stayed home alone a lot, and words filled up my afternoons and evenings after school. Reading, writing, and music were life. Reading and studying sacred scriptures were equally important to me, and I still actively struggle with this in the context of my writing.

In my family and in my culture, storytelling is vitally important. The oral histories of our people, many that have not been documented in writing, have been carried and transported through generations in spite of genocide, conquest, migration due to displacement, and assimilation. I highlight storytelling as a key cultural component because for many with indigenous root to this hemisphere, it is our stories that teach us who we are and where we come from, inspire us to love, and kept us alive for all these centuries.

While in college, my identity as Chicana shifted to Xicana. It became Xicana with an X to give respect and acknowledge the strength and prominence of the X in the Nahuatl languages. Sometimes I might even vary the spelling Xicanx to be inclusive of two-spirit relatives.

I am Xicana 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. There will never be a month I am not Xicana. I am a woman descended from Mexicans born in the United States. I am proud of my upbringing and the beauty and complexity of my background. Here’s a snippet of poetry from a poem entitled “Poem for the Fat Feminists Who Gave Me Back My Body” that celebrates my ancestors and who I am:

Fat girl

Poeta

Goddess

Indigena

Diosa Coatlicue

You gave me back my body

It runs deep, your blood

through these veins

No amount of hate

No amount of maiming

No amount of rape

Could water down this DNA

Brenda Vaca, a Xicana poet, author, and independent publisher, earned her B.A. in English at U.C. Berkeley with a minor in Creative Writing. Later she went on to graduate school in Berkeley earning a Master of Divinity and a Master of Arts in Biblical Languages from the Pacific School of Religion and Graduate Theological Union. She hosts the Instagram Live series Friday Fire.