by Jane Friedman, reprinted with permission.

by Jane Friedman, reprinted with permission.

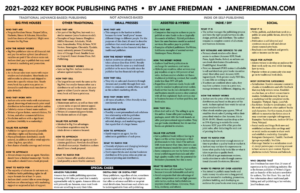

Since 2013, I have regularly updated this informational chart about the key book-publishing paths. It is available as a PDF download, ideal for photocopying and distributing for workshops and classrooms, and the full text is also below.

One of the biggest questions I hear from authors today: Should I traditionally publish or self-publish?

This is an increasingly complicated question to answer because:

There are now many varieties of traditional publishing and self-publishing, with evolving models and diverse contracts.

You won’t find a universal, agreed-upon definition of what it means to traditionally publish or self-publish.

It’s not an either/or proposition; you can do both. Many successful authors, including myself, decide which path is best based on our goals and career level.

Thus, there is no one path or service that’s right for everyone all the time; you should take time to understand the landscape and make a decision based on long-term career goals, as well as the unique qualities of your work. Your choice should also be guided by your own personality (are you an entrepreneurial sort?) and experience as an author (do you have the slightest idea what you’re doing?).

My chart divides the field into traditional (advance-based) publishing, small presses, assisted publishing, indie or self-publishing, and social publishing.

Traditional publishing (the big guys and the little guys):

I define traditional publishing primarily as receiving payment from a publisher in the form of an advance. Whether it’s a Big-Five publisher or a smaller house, the traditional publisher assumes all financial risk and typically invests in a print run for the book. The author may see no other income from the book aside from the advance; in today’s industry, it’s commonly accepted that most book advances don’t earn out. However, authors do not have to pay back the advance; that’s the risk the publisher takes.

Small presses.

This is the category most open to interpretation among authors. For the purposes of this chart, I define small presses as publishers who take on less financial risk because they pay no advance and avoid print runs. Authors must exercise caution when signing with small presses; some mom-and-pop operations offer little advantage over self-publishing, especially when it comes to distribution and sales muscle. Also, think carefully before signing a no-advance deal or digital-only deal, which are sometimes offered even by the big traditional houses; you may not receive the same support and investment from the publisher on marketing and distribution. The less financial risk the publisher accepts, the more flexible your contract should be, and ideally they’ll also offer higher royalty rates.

Assisted and hybrid publishing.

This is where you pay to publish and enter into an agreement or contract with a publishing service or a hybrid publisher. Once upon a time, this was called vanity publishing, but I don’t like that term. Costs vary widely (low four figures to well into the five figures). There is a risk of paying too much money for basic services or purchasing services you don’t need. Some people ask me about the difference between a hybrid publisher and other publishing services. Usually there isn’t a difference, but click here for more details. The Independent Book Publishers Association also offers a set of criteria for evaluating hybrid publishers. Click here to read.

Indie or DIY self-publishing.

I define this as publishing on your own, where you essentially start your own publishing company and directly hire and manage all help needed. Here’s an in-depth discussion of self-publishing.

Social publishing.

Social efforts will always be an important and meaningful way that writers build a readership and gain attention, and it’s not necessary to publish and distribute a book to say that you’re an active and published writer. Plus, these social forms of publishing increasingly have monetization built in, such as Patreon.

Feel free to download, print, and share the chart; no permission is required. It’s formatted to print perfectly on 11″ x 17″ or tabloid-size paper. Below is the full text from the chart.

Big Five Houses (Traditional Publishing)

Who they are

Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Hachette, Simon & Schuster, Macmillan (each has dozens of imprints). Might soon become the Big Four if Penguin Random House does in fact acquire Simon & Schuster (deal requires regulatory approval).

How the money works

Big Five publishers take on all financial risk and pay the author up-front (an advance); royalties are paid if the advance earns out. Authors don’t pay to publish but may need to invest in marketing and promotion.

How they sell

The Big Five have an in-house sales team and meet with major retailers and wholesalers. Most books are sold months in advance and shipped to stores for a specific release date. Nearly every book has a print run; print-on-demand may be used when stock runs low or sales dwindle.

Who they work with

- Authors who write works with mainstream appeal, deserving of nationwide print retail distribution in bookstores and other outlets.

- Celebrity-status or brand-name authors.

- Writers of genre fiction, women’s fiction, YA fiction, and other commercial fiction.

- Nonfiction authors with a significant platform (visibility to a readership).

Value for author

- Publisher (or agent) pursues all possible subsidiary rights and licensing deals.

- Physical bookstore distribution nearly assured, in addition to other retail opportunities (big-box, specialty).

- Best chance of media coverage and reviews.

How to approach

Almost always requires an agent. Novelists should have a finished manuscript. Nonfiction authors should have a book proposal.

What to watch for

- The majority of advances do not earn out.

- Publisher holds onto all publishing rights for all major formats for at least 5+ years.

- You don’t control title or cover design.

- Authors may be unhappy with marketing support or surprised at lack of support. Click to read the questions to ask your publisher before you sign a deal.

Other Traditional Publishers

Who they are

Not part of the Big Five, but work in a similar manner (similar business model).

Examples of larger houses: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Scholastic, Workman, Sourcebooks, John Wiley & Sons, W.W. Norton, Kensington, Chronicle, Tyndale, many university presses (Cambridge, Univ of Chicago Press). Smaller houses: Graywolf, Forest Avenue Press, Belt Publishing.

How the money works

Same as Big Five. Author receives an advance against royalties.

How they sell

The largest houses work the same as the Big Five, but smaller houses often use a distributor to sell to the trade. Ask your agent or editor if you’re unsure. Nearly every book will have a print run.

Who they work with

- Authors who write mainstream works, as well as those that have a more niche or special-interest appeal.

- Celebrity-status or brand-name authors.

- Writers of commercial/genre fiction.

- Nonfiction authors of all types.

Value for author

Identical to Big Five advantages. Sometimes acquisitions may be ideals driven or mission focused.

How to approach

Doesn’t always require an agent; see submission guidelines for each publisher. Novelists should have a finished manuscript. Nonfiction authors should have a book proposal.

What to watch for

Smaller houses offer smaller advances (and possibly a more flexible contract).

Small Presses

Who they are

This category is the hardest to define because the term small press means different things to different people. For the purposes of this comparison chart, it’s used to describe publishers that avoid advances and print runs. Thus, they take on less financial risk than a traditional publisher.

How the money works

Author receives no advance or possibly a token advance (less than $500). Royalty rates may look the same as a traditional publisher or be more favorable since the publisher has less financial risk upfront.

How they sell

They rely on sales and discovery through Amazon and possibly through their own direct-to-consumer or niche efforts, as well as the author’s marketing efforts.

Who they work with

All types of authors. Often friendly to less commercial work.

Value for author

Possibly a more personalized and collaborative relationship with the publisher.

With well-established small presses: editorial, design, and marketing support that equals that of a larger house.

How to approach

Rarely requires an agent. See the submission guidelines of each press.

What to watch for

- Diversity of players and changing landscape means contracts vary widely.

- Don’t expect brick-and-mortar bookstore distribution if the press relies on print-on-demand printing and distribution.

- Potential for media or review coverage declines without a print run.

- Carefully evaluate a small press’s abilities before signing with one. Protect your rights if you’re shouldering most of the risk and effort.

Assisted and Hybrid Publishing (Self-Publishing)

Who they are

Companies that require you to pay to publish or raise funds to do so (typically thousands of dollars). Hybrid publishers have the same business model as assisted services; the author pays to publish.

Examples of hybrid publishers: SheWrites, InkShares; examples of assisted service: Gatekeeper Press, Matador

How the money works

- Authors fund book publication in exchange for assistance; cost varies.

- Hybrid publishers pay royalties; other services may pay royalties or up to 100 percent of net sales. Authors receive a better cut than a traditional publishing contract, but usually make less than DIY self-pub.

- Regardless of promises made, books will rarely be stocked in physical retail outlets.

- Each service has its own distinctive costs and business model; secure a clear contract with all fees explained. Such services stay in business because of author-paid fees, not book sales.

How they sell

Most don’t sell at all. The selling is up to the author. Some offer paid marketing packages, assist with the book launch, or offer paid promotional opportunities. They can get books distributed, but it’s rare that books are pitched to retailers.

Value for author

Get a published book without having to figure out the service landscape or find professionals to help. Ideal for authors with more money than time, but not a sustainable business model for career authors.

Some companies are run by former traditional publishing professionals and offer high-quality results (with the potential for bookstore placement, but this is rare).

What to watch for

Some services call themselves “hybrid” because it sounds fashionable and savvy.

Avoid companies that take advantage of author inexperience and use high-pressure sales tactics, such as AuthorSolutions imprints (AuthorHouse, iUniverse, WestBow, Archway, and others).

Indie or DIY Self-Publishing

What it is

The author manages the publishing process and hires the right people/services to edit, design, publish, and distribute. The author remains in complete control of all artistic and business decisions.

Key retailers and services to use

- Primary ebook retailers offer direct access to authors (Amazon KDP, Nook Press, Apple Books, Kobo), or authors can use ebook distributors (Smashwords, Draft2Digital, StreetLib).

- Print-on-demand (POD) makes it affordable to sell and distribute print books via online retail. Most often used: Amazon KDP, IngramSpark. With printer-ready PDF files, it costs little or nothing to start.

- If authors are confident about sales, they may hire a printer, invest in a print run, manage inventory, fulfillment, shipping, etc.

How the money works

- Author sets the price of the work; retailers/distributors pay you based on the price of the work. Authors upload their work for sale at major retailers for free.

- Most ebook retailers pay approx. 70% of retail for ebook sales if you price within their prescribed window (for Amazon, this is $2.99–$9.99). Ebook royalties drop as low as 35% if pricing is outside the norm.

- Amazon KDP pays 60% of list price for print sales, after deducting the unit cost of printing the book.

What to watch for

- Authors may not invest enough money or time to produce a quality book or market it.

- Authors may not have the experience to know what quality help looks like or what it takes to produce a quality book.

- It is difficult to get mainstream reviews, media attention, or sales through conventional channels (bookstores, libraries).

When to prefer DIY over assisted

- You intend to publish many books and make money via sales over a long period.

- You are invested in marketing, promotion, platform building, and developing an audience for your books over many years.

Social Publishing

What it is

- Write, publish, and distribute work in a public or semi-public forum, directly for readers.

- Publication is self-directed and continues on an at-will and almost always non-exclusive basis.

- Emphasis is on feedback and growth; sales or income can be rare.

Value for author

- Allows writers to develop an audience for their work early on, even while learning how to write.

- Popular writers at community sites may go on to traditional book deals.

Most distinctive categories

- Serialization: Readers consume content in chunks or installments and offer feedback that may help writers to revise. Establishes a fan base, or a direct connection to readers. Serialization may be used as a marketing tool for completed works. Examples: Wattpad, Tapas, LeanPub.

- Fan fiction: Similar to serialization, only the work is based on other authors’ books and characters. For this reason, it can be difficult to monetize fan fiction since it may constitute copyright infringement. Examples: Fanfiction.net, Archive Of Our Own, Wattpad.

- Social media and blogs: Both new and established authors alike use their blog and/or social media accounts to share their work and establish a readership. Examples: Instagram (Instapoets), Tumblr, Facebook (groups especially), YouTube.

- Patreon/patronage: Similar to a serialization model, except patrons pay a recurring amount to have access to content. Popular platforms include Patreon and Substack.

Special cases

Amazon Publishing

With more than a dozen imprints, Amazon has a sizable publishing operation (1,000+ titles per year) that is mainly approachable only by agents. Amazon titles are sold primarily on Amazon, since most bookstores are unwilling to carry their titles.

Digital-only or digital-first

All publishers, regardless of size, sometimes operate digital-only or digital-first imprints that offer no advance and little or no print retail distribution. Sometimes such efforts are indistinguishable from self-publishing.

Jane Friedman has 20 years of experience in the publishing industry, with expertise in digital media strategy for authors and publishers. She is the publisher of The Hot Sheet, the essential newsletter on the publishing industry for authors, and was named Publishing Commentator of the Year by Digital Book World in 2019. In addition to being a columnist for Publishers Weekly, Jane is a professor with The Great Courses, which released her 24-lecture series, How to Publish Your Book. Her book for creative writers, The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press), received a starred review from Library Journal.

Jane, this is extremely valuable. Thanks for providing this service.